The architect David Costanza is our 2025 Lily Auchincloss Rome Prize Fellow and assistant professor in the Department of Architecture at Cornell University. His work rethinks the assumptions behind sustainable building, pushing beyond carbon metrics to consider the human, historical, and technical dimensions of material use. From visits to quarries across Italy to conversations with medievalists, Costanza navigates between research and practice, tradition and innovation, to explore how structural stone might once again play a central role in architecture’s future.

In addition to presenting this interview, the Academy congratulates Costanza for winning the 2025 Architectural League Prize for Young Architects + Designers, announced last week.

Your project draws connections between stone and materials like mass timber in contemporary low-carbon construction. What preindustrial building methods are most applicable to us today?

Yes, that is correct. I like the distinction your question makes between building materials and building methods, since the application of different materials impacts how you build. The Building Construction Lab that I direct at Cornell University is exploring the wide use of preindustrial building methods and materials. In this pursuit, I am not alone, as many colleagues and architects share an interest in natural and low-carbon materials. This turn came from the realization that the construction industry’s most significant contribution to climate change is the carbon released during construction. With the shift from operational energy and energy reduction to embodied carbon and decarbonization, the conversation around sustainability gravitated toward natural and nonindustrialized materials that help reduce carbon.

While I share this sentiment, my interest in low-carbon materials and preindustrial building methods mostly calls attention to the impact these changes will have on labor conditions on the construction site. Since the advent of fossil fuels, energy consumption has been directly linked to increased carbon and, conversely, a reduction of physical labor. For example, steel, which historically required enormous amounts of carbon to produce, allowed for rapid construction with fewer laborers. Conversely, natural materials like straw and rammed earth, which are very low carbon, continue to be labor intensive. In this context, I’ve been rethinking the tools and techniques such materials require. Considering that labor-intensive techniques are more prone to human exploitation, I argue that decarbonization cannot be decoupled from labor practices at the construction site.

The push for decarbonized construction is shaping architecture’s future. How do you envision stone fitting into this movement at an industry-wide scale?

Using locally sourced, minimally processed stone can replace industrialized high-carbon alternatives, especially when coming in contact with the ground, where other low-carbon natural building materials struggle. A simple example might be one or two stories erected on a stone foundation, topped with a mass timber superstructure. This concept borrows from the “5 over 2” building type, a hybrid construction method where a building consists of two stories of fire-resistant construction (like concrete or steel) followed by five stories of lighter, often wood-framed construction. This is North America’s most widely used construction technique for housing, particularly affordable housing. Models for structural stone in construction can be found in the work of Pierre Bidaud of the Stone Masonry Company and architect Gilles Perraudin’s stone buildings in France and Switzerland. Yet hybrid systems that include stone are rare in contemporary construction, although many examples exist in history.

Has the architectural history and material culture of Rome—a city built on and from stone, from ancient ruins to Baroque façades—influenced your thinking?

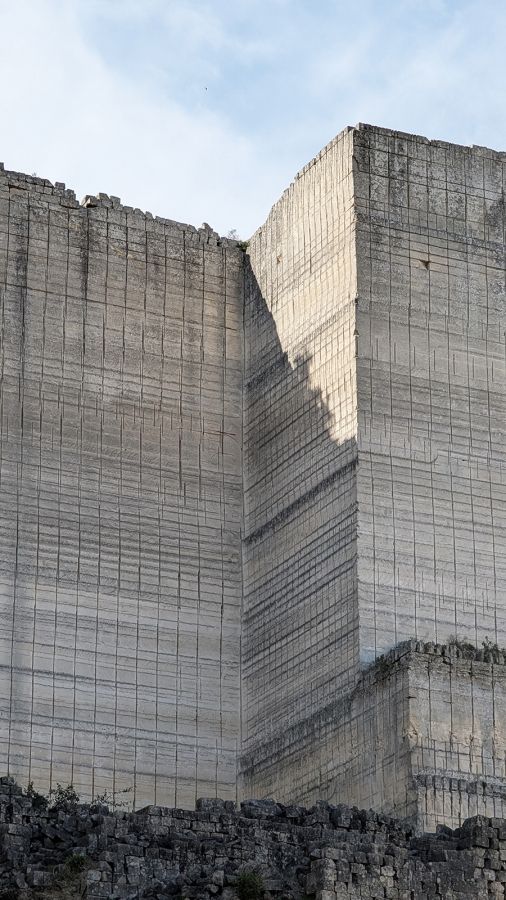

Living in Rome and visiting stone buildings and quarries across Italy—from the marble quarries in Carrara in the North to the Travertine quarries in Tivoli outside Rome and finally to the limestone quarries of Matera in the South—have highlighted the widespread use of stone in anonymous contexts, contrasting with the highly referenced and canonized buildings constructed by celebrated artists and sculptors. Using marble as revêtement or veneer reflects the most common attitude toward stone today, which is nonstructural or reusable, involves significant processing, and has a global shipping footprint that produces large amounts of carbon and waste.

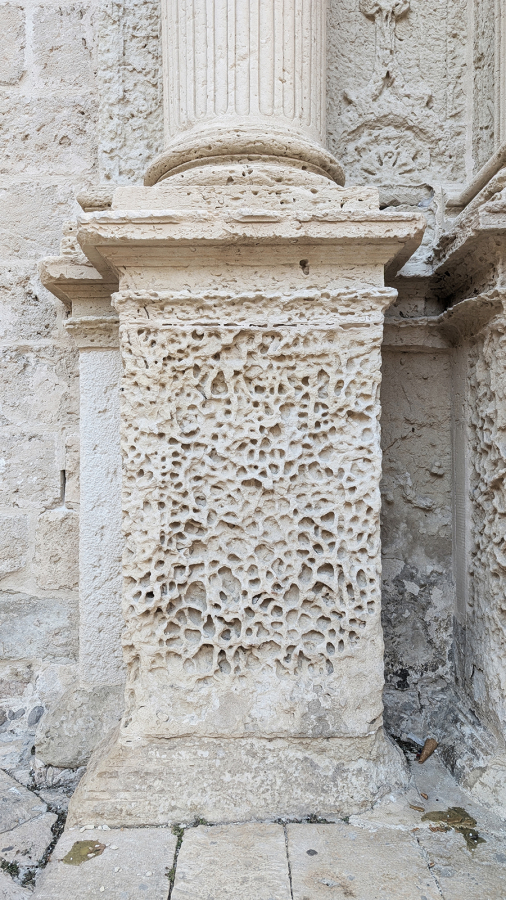

In contrast, the limestone quarries, some of which still operate today, outside Matera, extract construction-ready blocks directly from the earth for deployment just a few miles away from the city. These blocks, used structurally, create an incredible array of building typologies based on the same stone. Many of these buildings are anonymous, products of a building culture that has developed over centuries. This perspective encourages a critical distance toward the value typically ascribed to many early modern stone buildings, celebrating instead the ordinary and everyday use of a local building material.

Of course, there is also something to be said about the way of thinking about reuse prompted by certain stone buildings that, by maintaining the integrity of the stone as monolithic blocks, were quarried across time. This intelligence was not exclusive to stone since every scrap of glass and loose brick was reused.

What is your most surprising discovery since arriving at the Academy?

I was pleasantly surprised to learn more about the Academy, its history, and its role over the last 130 years in advancing knowledge production and critical discourse. The number of important architectural figures who have participated in and contributed to AAR is particularly striking. It is not every day that Liz Diller unexpectedly strolls into a room, allowing for engagement in a way that is impossible in any other context.

How have your interactions with this year’s fellows and residents influenced your work or changed your perspective??

The community at the Academy has been lovely and has helped me position my work within broader histories and contemporary debates. My conversations with archaeologists and medievalists have enriched my understanding of various material cultures throughout time, illuminating moments of change and transition that have significantly impacted how people built and the materials they used. These exchanges make me question how I position my work within the history of my discipline. What types of knowledge are reflected in the material and construction practices of the buildings I’ve visited and documented? What knowledge emerged from their creation?

The buildings that interest me embody a form of knowing that people primarily pass down through social practices and institutions, not typically recognized as sources of “architectural” knowledge. This type of knowledge is difficult to define in words because it is instead “known” in the body and developed heuristically. While in Rome, I have been trying to teach myself how to observe stone by immersing myself in the techniques used in its production.

The title of your project, “Bending Stone,” suggests a tension between stone’s perceived rigidity and its potential adaptability. What does “bending” mean in this context?

I initially intended the title to be understood in its most technical sense. Advancements such as prestressing through post-tensioning foster renewed interest in stone while broadening its potential applications. Prestressed concrete panels have become prevalent with concrete, enhancing the latter’s structural capacity while minimizing the amount of required material. It does so by placing the material under sufficient compression, counteracting the tensile stresses that would typically arise under loading. This precompression boosts the concrete’s resistance to cracking and exploits its compressive strength. Similarly, prestressed stone allows for the use of stone in bending—in tension—rather than in conventional funicular stone structures, which work in compression, thus advancing the possibilities for contemporary stone construction.

I now understand the title to mean something broader: it suggests either adapting or distorting the role of stones in modern construction. For example, limestone is crushed into a powder and burned through a fossil-fuel-intensive process to produce cement. As a result, limestone loses its natural structural capacity and takes on a secondary role in concrete’s narrative. With this research, I intend to bend stone’s role in construction by acknowledging its technical properties and environmental impact.