In her year as a 2025 Rome Prize Fellow, the San Francisco–based writer Selby Wynn Schwartz, has been gathering fragments—of myth, of protest, of marine life and mineral extraction—and shaping them into a hybrid form she calls The Small Sea. Part novel, part poetic inquiry, her current work draws inspiration from the ancient city of Taranto, ecological transfeminism, and the myth of Persephone, reimagined for a world contending with environmental devastation and extractive histories. In this interview, Schwartz reflects on the experimental contours of her writing practice, her intellectual and activist networks across Italy and Europe, and the role of lyrical queer ecologies in her evolving vision.

During your time as a Rome Prize Fellow, how has your immersion in Italy influenced your research and writing process for “The Small Sea”?

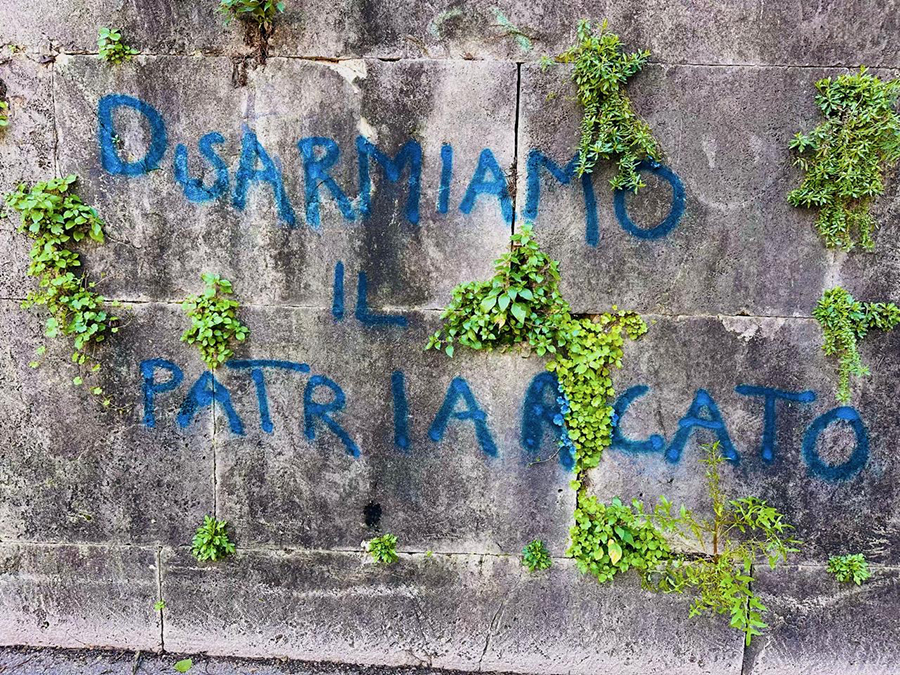

To create a fragmentary, hybrid, experimental book, I gather research in a wandering, somewhat chimerical way: in a single day I might be reading about why Mediterranean oysters change genders, how the island of Elba got its name, and where in Rome will the next transfeminist protest take place. Sometimes I am in the library, solitary with a stack of books; sometimes we are in the streets, singing together against fascism. The American Academy has been home to a warm, thoughtful, diverse, encouraging, lively community this year. And I am deeply appreciative of the scholars, activists, and artists connected to Taranto who have been teaching me how to see not only its histories but also its possible futures.

What drew you to Taranto as a setting for the novel, and how does its history shape your narrative?

Taranto is so layered with histories that the silt & shards of them are everywhere. There were Paleolithic peoples in the region who left figurines of women carved in bone; there was a Spartan colony in the era of Magna Grecia; there were centuries of seagoing in the Gulf of Taranto. In fact, this is one way to tell the story of the city: Taranto has an internal Mar Piccolo, a small sea, and it gives out onto a Mar Grande, a great sea in the Gulf of Taranto, which opens into the Ionian Sea, which belongs to the Mediterranean, which is a sea shared by places from Gaza to Sicily, from the Libyan coast to the region of Lazio. Thus decisions made in Rome—to colonize other lands, for example, or not to save boats of people seeking asylum—affect all of the shores that touch these seas.

Thus when the decision was made, in postwar Italy, to ‘modernize’ the South by building a gigantic steel mill in Taranto, where it could cool itself with the waters of the Mar Piccolo and discharge its wastes into the surrounding seas, soil, and air, the devastating pollution rippled out far beyond one small sea. In 2022, the UN declared Taranto a “sacrifice zone.” But we know that these histories are not limited to one city, to one sea. This is why ecological transfeminism is so inspiring to me: it is a ‘no borders’ movement, in many senses of those words.

Your book reimagines the story of Persephone. What does this myth reveal about our contemporary struggles with industry, ecology, and agency?

The ancient Greek Homeric Hymn to Demeter tells the story of Persephone, a girl who went out into a meadow one morning to pick flowers with her companions only to be taken, against her will, by the god of the underworld. That word—taken—is the key to so many stories about how our world has come to be the way that it is. No girl, no person, no community, no territory of lands or waters would freely choose the violence of being taken like that. Persephone wanted sunlight and crocuses, not marriage to a god of death who prized the dull shine of valuable ores over everything else. The people of Taranto in postwar Italy wanted to make their livings and have their futures, not unswimmable seas and lung diseases.

What follows this initial injustice is an egregious form of storytelling about whose fault it is, and a terrible settling down to the way things must be now. In other words, whoever is Persephone gets blamed for the violence that is done to her, and then—even though her mother Demeter searches ceaselessly for her, with feminist grief and rage, demanding justice—she is supposed to resign herself to this new reality. So when I am writing these interwoven stories of Persephone and Taranto, I am trying to make a fragmented sort of song against all of these kinds of being taken.

You describe “The Small Sea” as “lyrical queer ecologies.” How would you define this evocative phrase and how does it manifest in your writing?

Can I tell you how fascinating limpets are? The tiny teeth of limpets are made of the strongest biomaterial that exists, so that they can scrape their tongues across rocks to eat algae. Like oysters, limpets can change genders. To ‘limpetize’ means not to be descended from some single original limpet, but rather to change the shape of a shell over time, to adapt an outer form to the word—something that has happened, evolutionarily, to a quite diverse group of gastropod mollusks. So when you look into a tidepool and see a limpet, it is a marvelous thing! Even the rock that a limpet lives on is striated all over with the lines left by its teeth—so perhaps I could say that a limpet writes their own lyrical queer ecologies, and I am merely trying to trace some of those.

You have been active during your fellowship term—especially this month—speaking at the Academy, Villa Medici, and Librairie Stendahl in Rome, as well as in Siena, Venice, and Paris. How did these opportunities arise?

I am grateful to the community of the American Academy for the opportunity to participate in conversations around feminism, ecology, queer history, and fragmentary forms. This spring, I was honored that Academy invited me to take part in NICHE (The New Institute Centre for the Environmental Humanities) at Ca’ Foscari University in Venice. Other opportunities arose from the interconnected constellations of artists, scholars, and transfeminist activists that I am fortunate to know; for example, thanks to the Queer Kinship Network, I gave both the annual Virginia Woolf lecture at the Università per Stranieri in Siena and a keynote speech at the Queer Kinship conference at Oxford.

Whenever I can, though, I prefer to share the stage-light as much as possible—to be one voice among many—as when the fantastic Suzette Robichon organized a collective reading of the French translation of my book After Sappho at the Maison de la Poèsie in Paris. Current Villa Medici resident Clovis Maillet included me in a presentation on MOTHA: Trans Hirstory in 99 Objects; now we are collaborating with black cat day dream on new versions of shorelines for the Festival des Cabanes. But let me say that I would not have met Clovis unless Sheila Pepe had introduced us one evening in the cortile of the Academy!