The following essay by Denise Costanzo, associate professor of architecture at Pennsylvania State University and a 2015 Rome Prize Fellow in modern Italian studies, accompanies the American Academy’s fall exhibition From Las Vegas to Rome: Photographs by Iwan Baan, on view October 6–November 27, 2022.

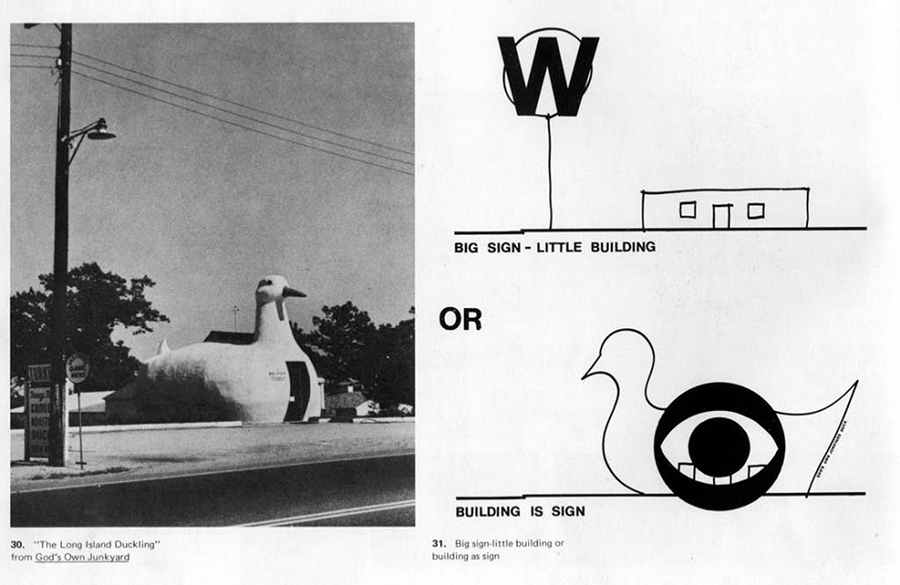

What a cheeky move when Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and their graduate assistant Steven Izenour drew a glittering, incongruous line from Rome to Las Vegas (with Venturi’s Sharpie) in 1972. Their reflective explorations, along with studio work by their students at Yale, became a book that eventually tied with Venturi’s Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (1966) for the position of twentieth-century architecture’s second most influential manifesto. (Le Corbusier’s Vers une architecture of 1923 holds the top spot.) Learning from Las Vegas is a quick, captivating read dominated by neon-lit visuals, brief and punchy prose, ducks and decorated sheds. Still feisty at fifty, this perfect polemic for the post-’68 generation has entered architecture’s canon.

The book’s simultaneously rebellious and legitimate stature stands on Italian foundations, the deepest ones Roman. Learning from Las Vegas gleefully pairs the capital of both Christendom and classical pieties with Sin City, in all its cheap, tawdry vulgarity. How? The authors justify Vegas first: “learning from everything” in a nonjudgmental way (initially) is “a way of being revolutionary for an architect.” Italy appears a page later, under the heading “Billboards Are Almost All Right”: “The Italian landscape has always harmonized the vulgar and the Vitruvian; the contorni around the duomo, the portiere’s laundry room across the padrone’s portone, Supercortemaggiore [gas station] against the Romanesque apse.” After this image of impurity’s delights, they rebuke their fellow architects: “Naked children have never played in our fountains, and I. M. Pei will never be happy on Route 66.” Italy illuminates the failures of a discipline producing uninviting plazas and culturally alienated leaders.

Most of the book’s Italian references are brief: the Palazzo Farnese is called a decorated shed; the ironies in the romanità of Caesar’s Palace are unpacked; tourism as neopilgrimage, the Strip an analogue of the Forum. These can zoom past because of an earlier section provided the theory of the case. “From Rome to Las Vegas” presents both cities as archetypes of communication modes attuned to a transportation system’s given speed and scale, where clashing local and supernational conditions produce “violent juxtapositions.” Giambattista Nolli’s 1748 map of Rome is explained succinctly as a method of urban representation, a Las Vegas postcard layered over his Piazza Navona in the book’s figure 17. The pairing is deadpan, defiant: no big deal. It is obvious that Italy’s historic cities and the commercial strip are related. And not obvious; quite a big deal.

Learning from Las Vegas is dominated by roadside signage, casino halls, supermarket parking lots, single-family suburban housing—all largely un-Italian phenomena. The book’s call to look, understand, and only then judge the environments wrought by twentieth-century commercial culture could have been framed in exclusively North American terms, like Jane Jacobs’s illustrations of urban vibrancy a decade earlier. But in Learning from Las Vegas, Italian examples are essential, and cannily strategic. Architects who despised shopping centers could hardly resist a piazza; appealing to these irrefutably delightful images of civic venustas, then pointing out their messy mix of high and low, halted outraged protestations and kept skeptics reading, despite themselves. Rome was a ballast that anchored Venturi and Scott Brown’s riposte to Peter Blake’s billboard-hating book God’s Own Junkyard of 1964. Without the weight of Italy behind its provocations, the argument of Learning from Las Vegas would have been little more than de gustibus non disputandum est, its sharp teeth blunted.

Venturi and Scott Brown deftly wielded Italian references based on direct, informed relationships with the country. Hardly unusual for twentieth-century Anglophone architects; what makes their attitudes distinct is how intimate familiarity becomes a mix of veneration and irreverence, tradition and today. Venturi was a son and grandson of Italian immigrants and traveled there twice before his famous Rome Prize fellowship of 1954–56. He ritually celebrated the anniversary of his first day in Rome, and an encyclopedic knowledge of Italian sites pervades his work. But these associations were selective and critical. His parents were suburban Quakers who left behind their ethnic neighborhood, Catholicism, and even pasta, but held onto opera, art, and nostalgia for their native regions of Abruzzo and Puglia. In Italy, Venturi saw baroque spectacle through the all-American lens of Broadway and the circus; he had also read Carlo Levi and recognized the not-yet-Hollywood-famous Sophia Loren in the Forum.

Venturi’s first visits to Italy sparked his interests in context (his master’s thesis topic) and the contrast of its urban spaces’ vitality with American cities. These topics drove his Rome Prize research, but he valued the fellowship (won on his third try) because he saw it impacting the careers of architects and mentors George Howe and Louis Kahn. A Princeton architectural historian and a pioneering scholar of the Beaux-Arts, Donald Drew Egbert, taught how the French Rome Prize tradition constructed elite architectural status. He understood the power references to Rome had for architects, the disciplinary authority emanating from its aura.

Many of Venturi’s early interests, such as Townscape urbanism promoted by the British journal Architectural Review, overlapped with Denise Scott Brown’s milieu. She left South Africa to study at the Architectural Association in London in 1952, and there absorbed the Independent Group’s enthusiasms for both advertising imagery and Italian mannerism. Scott Brown, whose family were also transcontinental immigrants (Jewish Eastern European, in her case), intended to return home and devote her career to improving the cities and environments she knew best. Lessons extracted from London and Palladio were meant for Johannesburg and Cape Town.

Her most intensive Italian experiences followed Venturi’s when she and her first husband Robert Scott Brown attended the 1956 Congrès International d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM) summer school in Venice for two months of intense lectures, discussions, and design charettes with major Italian figures at the Istituto Universitaria di Architecture di Venezia. At Ludovico Quaroni’s suggestion, they spent another two months working for Giuseppe Vaccaro in Rome, a far more immersive and quotidian Italian experience than Venturi’s. Their focus in Italy was urban, contemporary, and pragmatic: their CIAM group project studied transportation networks connecting Venice and Mestre, and in Vaccaro’s office they worked on the master plan for Rome.

These common interests in urbanism, mannerism, popular culture—and Italy—drew together a widowed Scott Brown and Venturi in Philadelphia in 1960. But a shared outlook on what mattered, and why, shaped how Italy was deployed in Learning from Las Vegas. They adored Italian cities, architecture, and culture, and fully understood their cultural importance, but did not consider them intrinsically authoritative. Italy was instructive because of how its cities worked—or, more precisely, certain parts of certain cities, within a set framework. Pedestrian-friendly piazze, narrow viali, and legible façades in a centro storico met a specific set of social and infrastructural needs. These places can also fail within a changed context, like a tsunami of automobiles and tourists. This question of functionalism—how (or whether) forms relate to a particular use—was one of Scott Brown’s most enduring interests. It was a live issue during the 1950s at CIAM and among the social planners Scott Brown studied with in graduate school. She (and they) wrote about it for decades, adopting “functionalist” as a label. Their call to “learn from everything” was neither unbounded nor directionless; it was a mission to clarify how the world operates, so architects can help make it work better.

Venturi and Scott Brown scrutinized and leveraged the referential power of Italy with critical, unenthralled eyes. In this, their model was the same one echoed in their book title. Learning from Las Vegas recalls Le Corbusier’s “La leçon de Rome (The Lesson of Rome),” the central chapter of Vers une Architecture and one with a very similar view of Italy. Le Corbusier wielded the Beaux-Arts’ epicenter against itself by celebrating an academically heretical Michelangelo, insisting that Rome’s truths could only be revealed by new approaches to the city, and declaring how much better the Pantheon would be without its marble cladding. In other words: he used a bold, irreverent take on a venerated authority to make his revolutionary ideas harder to dismiss. Sound familiar?

Among its many other forms of influence, Learning from Las Vegas further increased Italy’s (extensive) space on the bookshelf of twentieth-century architecture. It amplified established assumptions that important architectural thinkers can knowingly invoke Rome, and how effective it is to coat any radical new idea in Italian legitimacy. But what the book did differently was just as important, if not more, fifty years later. The web of connections Venturi and Scott Brown drew was an invitation to roll our eyes at whatever reasons we hear for the validity of any received authority. They remain models of how to approach any source of power, withholding obeisance and judgment, to observe, question, and leverage the lessons we formulate for our own ends.