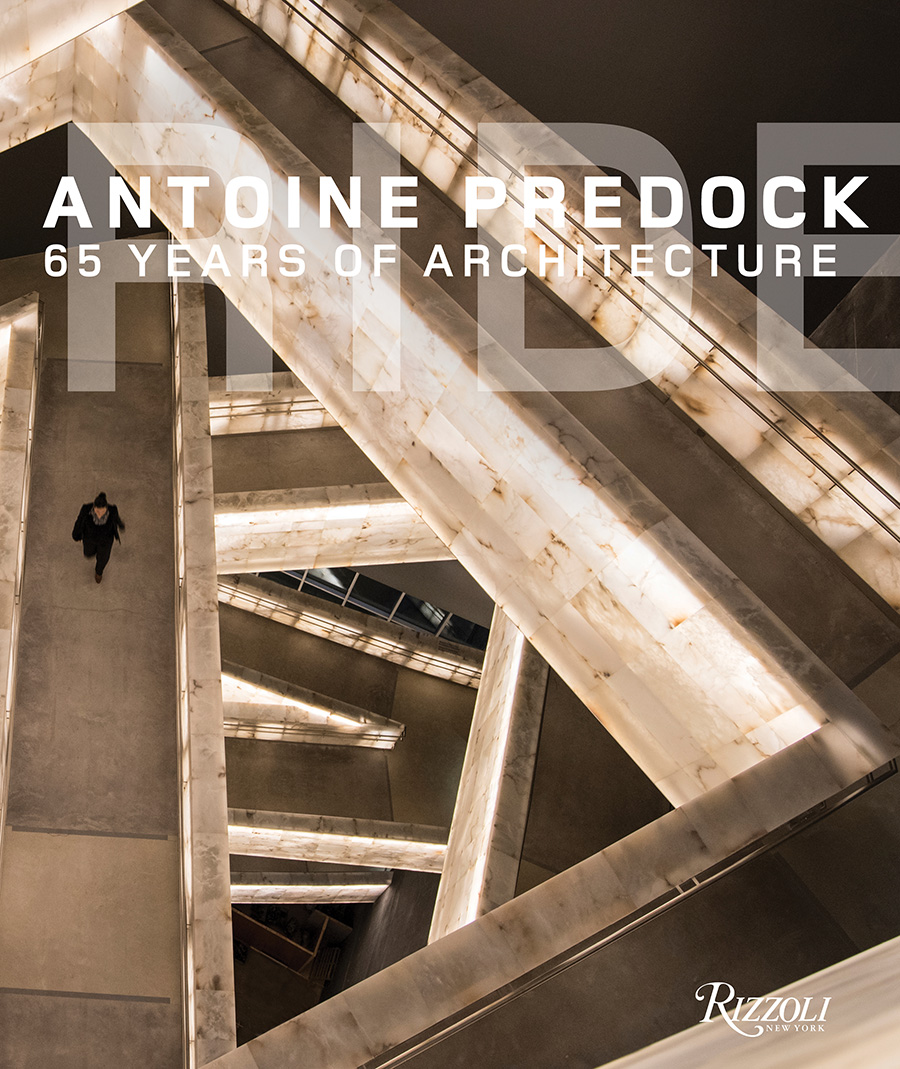

A new monograph from Rizzoli surveys the life and career of Antoine Predock, including his time at the American Academy as a Rome Prize Fellow in 1984–85. Predock, an acclaimed American architect whose work brought Frank Lloyd Wright–style modernism into new directions, completed the tome not long before his death in March of this year. The result is thrilling.

In Ride: Antoine Predock: 65 Years of Architecture, Predock devotes fifteen pages to his Rome Prize fellowship, and we naturally pay special attention to them here. Featuring intimate reflections about Rome and peppered with his drawings and sketches—by our count, over fifty of them—this section is so visually dense and diaristic that you feel as if you are peeking into the author’s mind. (You will have to buy the book if you want the full effect.)

Predock had two decades as a practicing architect under his belt when he won the Rome Prize. With the fellowship, “my everyday life [went] on pause,” he wrote, “immersed in a new (old) world, amid the strata, where the man-made dissolves through time into a geological blur, where natural landscapes have had order imposed upon them that is subtle and extraordinary, all haunted by an ancient presence.”

At the Academy, Predock constantly traveled in the city of Rome and beyond, always documenting his surroundings, either with a video camera or with his pastels and brush pen. Sketching and recording daily, “[he] learned to trust in the innocence of the encounter and the translation of that encounter into an innocent mark.”

He recounts, for example, how he visited the subterranean Mithraeum of the Basilica of San Clemente, armed with an Academy permesso. The shape of the plan of this place of pagan worship, he determined, evolved into the Latin cross plan. Snapshots shows trips he took to Villa Lante, Orvieto, Assisi, Florence, Venice, San Leo, and Pompeii. Frequently Predock was accompanied by the English architect and critic Alan Colquhoun, a 1985 Resident whom he befriended.

Predock’s humor is on full display in this monograph. The Tempietto is “Bramante’s little caged beast.” Casina Pio IV was the pope’s “crash pad.” Of the Vatican, Predock sardonically wrote, “How kind and minimal and austere Jesus was.” He also recounts a trip to the Pantheon—in his phrasing, the “Mothership”—on a rainy day and seeing two Japanese tourists calmly standing under the oculus with their umbrella unfurled.

But the experience was deeply serious, too. “This Roman blurring of geology, landscape, and building has had a profound effect on my approach to architecture and has propelled me to seek the spirit of those layers, to delve into and even further explore the accreted deep time of every site, every Roadcut—even where not so obviously present,” he remarked. This urge to become so deeply intimate with a particular site became the “heart of [his] process” as an architect.

One feature of Rome’s built environment that struck Predock is the recycling of material. Take, for instance, his interest in the marble facing of the Fontana Acqua Paola (the Fontanone) that was “cannibalized from Trajan’s market.” Another inspiration was the effect of water in an urban setting, whether in Rome’s many fountains, in the basement of an apartment building where he witnessed the groundwater of the Tiber flowing over massive slabs of stone carved with Latin inscriptions, or in Tiberius’s grotto, “where the dialectic play of man-ordered water and the surf of the Mediterranean is made so explicit—water to water, imperial intention creating an aperture to the realm of the sea.”

While in Rome, Predock continued to work remotely on several projects in New Mexico, including Treaster-Grey House in Tesque, a house for Paul Lazarus in the same town, and the Heart Building for Barry Ramo’s cardiologist group. Later in the year, he won a design competition for the Nelson Fine Arts Center at Arizona State University—a commission that would propel his career to new heights.

The beautiful sketches he made during his fellowship were collected and published as Italian Sketchbooks (1985). One drawing of the Pantheon—impressively economical in its strokes—was used for the design of everything from baseball caps to dinner plates. The sketch also featured prominently in the Academy’s centennial campaign of the 1990s.

The effect of the Rome Prize on Predock’s career is hard to overstate. A colleague once remarked about his year in Rome: “He left here Tony and came back Antoine.” But we will conclude with his own words: “The deepest, most lasting thing I brought away was a vision of a kind of time travel. In Rome I found myself exposed, physically and conceptually, to the process of excavation.”

Ride: Antoine Predock: 65 Years of Architecture is published by Rizzoli and can be purchased here (hardcover, 692 pages, $125).