Christopher Howard is communications manager for the American Academy in Rome.

Fifteen years in the making, Painting in Fifteenth-Century Italy: “This Splendid and Noble Art” (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2023) is the latest scholarly achievement from the art historian Diane Cole Ahl. She was researching the book while serving as the 2013 James S. Ackerman Scholar in Residence in late September and October 2012.

Over the years, Ahl delved into cultural conservation, nanotechnology, and the study of pigments and materials, all of which expanded and matured the book’s ambitious scope. The book was extensively researched with travel to Italy and museums across Europe and the United States. Many of the works discussed in the book are found in churches and palazzi as well as museums, archives, and libraries. Ahl also considered manuscripts, tarot cards, and components of now-dismembered altarpieces.

A renowned scholar of Italian Renaissance art, Ahl taught art history at Lafayette College in Easton, Pennsylvania, until her retirement in 2018. She has authored monographs on Benozzo Gozzoli (1996) and Fra Angelico (2008) and edited collections of essays on Masaccio (2000) and Leonardo da Vinci (1995). With her coeditor Gerardo De Simone, Ahl published The Arts in Pisa during the Early Renaissance (2016) and Confraternities and the Visual Arts in Renaissance Italy: Ritual, Spectacle, Image with Barbara Wisch (2000).

AAR corresponded with Ahl over email. The author was kind enough to reply to a few questions.

What part of your book was researched at the Academy?

Although I returned to the Eternal City several times after my residency, my stay at the Academy was fundamental to the chapter on Rome. I had the invaluable opportunity to use the library, write, and study the city’s monuments and art. I visited certain churches repeatedly, most notably Santa Croce in Gerusalemme, which occupies a key place in the discussion. My guided tour of the church for the AAR community and the pertinent questions that were posed helped to clarify my ideas. I crossed the city many times to evaluate the works of fifteenth-century painters.

Most important of all, the Academy arranged my visits to sites that were closed or privately owned. Among them were the Corsia Sistina and the Palazzo dei Penitenzieri della Rovere (then the headquarters of the Cavalieri del Santo Sepolcro di Gerusalemme, and now the Four Seasons Hotel Columbus). I was able to visit rooms inaccessible to the public in the Musei Vaticani, including the Bibliotheca Graeca and Bibliotheca Latina, and to study Pinturicchio’s murals in the Sala dei Santi from the scaffolding while they were undergoing conservation.

What was your experience like as a Resident?

Being able to reside in a congenial, creative community of artists, writers, composers, musicians, and scholars was inspiring. Conversations at lunch and dinner provided opportunities to engage with the Fellows and Residents. It was enlightening to discuss their projects. Lectures, excursions, performances, and exhibitions organized by AAR under the direction of Christopher S. Celenza offered an extraordinary range of intellectual experiences. My apartment on the lush grounds of the beautiful Villa Aurelia provided a serene environment for reflection and writing. Gazing down at Rome from the Janiculum encapsulated the city’s rich history, a constant inspiration.

What other libraries, archives, or sites did you find most valuable during your research?

The James S. Ackerman Residency was one month long. Although I used the library for research and writing, I focused my time on seeing sites and works throughout Rome.

What was your most surprising or novel find?

I became convinced of the centrality of materials and techniques—often eclipsed by discussions of perspective and optical theory—to understanding and evaluating Quattrocento painting. Most artists were deeply engaged with the chemistry of their art, experimenting with different pigments, emulsions, glazes, and techniques to create dazzling effects. Having the opportunity to study Roman works in situ, especially from scaffolding, was astonishing. The most inventive painter in this regard was Pinturicchio, who incorporated parchment, papier-mâché, wood, and glass disks in his murals. Captions for the book’s illustrations as well as discussions in the text identify the materials and techniques of every work, attesting their importance to my conception of fifteenth-century painting. This is a significant contribution to the literature.

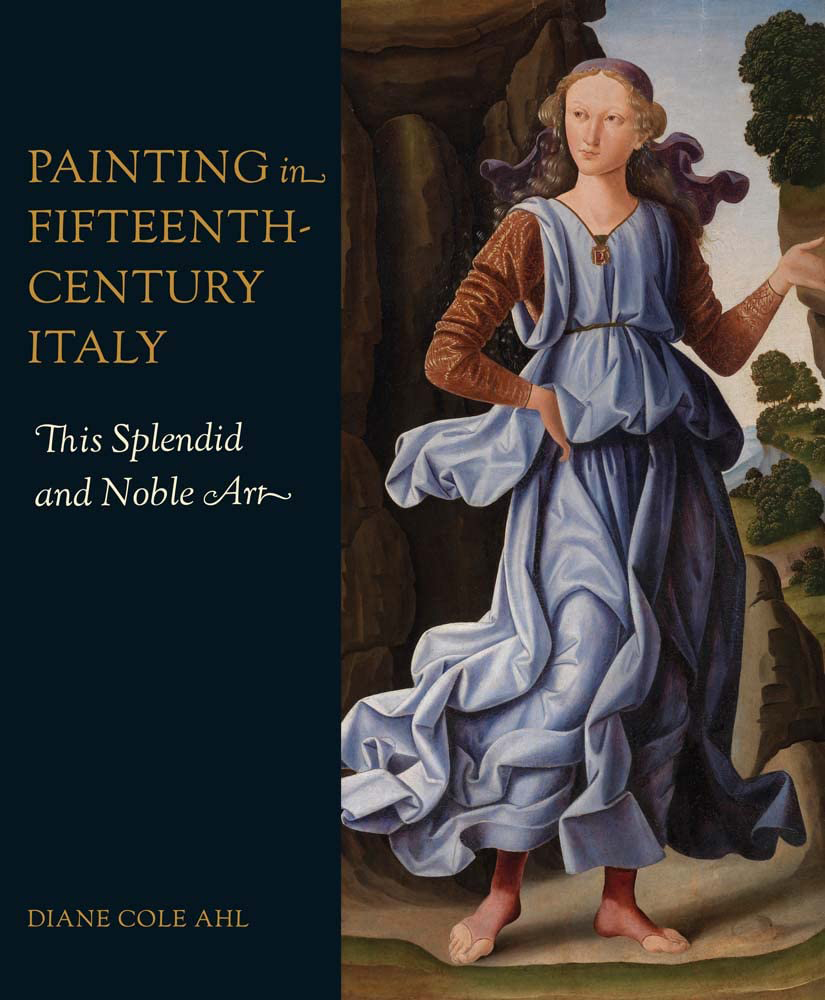

How did you choose the cover image?

The cover image is Clio, the Muse of History (ca. 1480–82, Galleria Corsini, Florence), executed by Giovanni Santi for the Temple of the Muses in the Palazzo Ducale of Urbino. Clio invites the reader to consider the title and open the book. The painting’s inscription, visible in the frontispiece, proclaims that she “sings the deeds of bygone times.” Giovanni Santi, the father of Raphael, was dismissed by Vasari as a “painter of no great excellence.” As an artist, author, and impresario of spectacles and triumphs, he was in fact a major figure in the brilliant Montefeltro court. He also traveled widely—travel is another major theme of the book—as is apparent in his Cronaca rimata (Rhymed chronicle, ca. 1482–87), a critical source for art historians. Giovanni Santi’s moving encomium to “this splendid and noble art” of painting inspired the book’s subtitle.