The first major retrospective of the work of Philip Guston (1949 Fellow, 1971 Resident) in over fifteen years opened in May 2022 in Boston. Organized by four museums—the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, Tate Modern in London, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston—Philip Guston Now presents the full scope of the artist’s convention-defying career. Its final iteration at the Tate Modern opens on October 5, 2023.

The retrospective gives us occasion to revisit Guston’s “lifelong intense romance” with Italy, in the words of the National Gallery of Art’s senior curator Harry Cooper, who, with the show’s Houston curator Alison de Lima Greene, spoke to AAR about Guston.

Guston made three trips to Italy in his lifetime, each coming at what the artist’s daughter Musa Mayer has called “crucial juncture[s]” in his practice: in 1948–49 as a Rome Prize Fellow; visits in 1960; and as an AAR Resident from 1970 to 1971. Alison de Lima Greene, a curator at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, believes that Guston’s trips to Italy and AAR were times “for contemplation and recharging, in every good way possible.” He was, she said, painting for himself. (Greene has her own Academy connection as the daughter of the late Sigrid de Lima and Stephen Greene, both 1954 Fellows.)

The 1948–49 Rome Prize Fellowship

The Rome Prize “got him, in 1948, exactly where he wanted to be,” said Cooper. There, Guston saw the works of Italian masters like Piero della Francesca, Fra Angelico, and Masaccio (especially the Brancacci Chapel frescoes in Florence) that would have been familiar to him from reproductions. “It says a lot about his historical turn of mind, his respect for tradition,” that he chooses to go, Cooper said. “The Italians were at the very pinnacle of art history for him.”

Yet Guston was acutely aware of New York trends around this time, stressed Greene. “He knows that the representational and narrative mode of his painting up to that moment is no longer part of the American vanguard.” Jackson Pollock, Guston’s high school classmate, had started his drip paintings. Rothko had created his upright rectangular format. “While he doesn’t want to imitate Pollock, he does want to be an important artist at the forefront of American art,” said Greene. “Going to Rome and traveling around and seeing the murals and paintings in the flesh was almost an act of exorcism, because then he doesn’t have to imitate the Italian masters any longer.” From that point on, Greene believes, they are internalized by him but no longer quoted in his work.

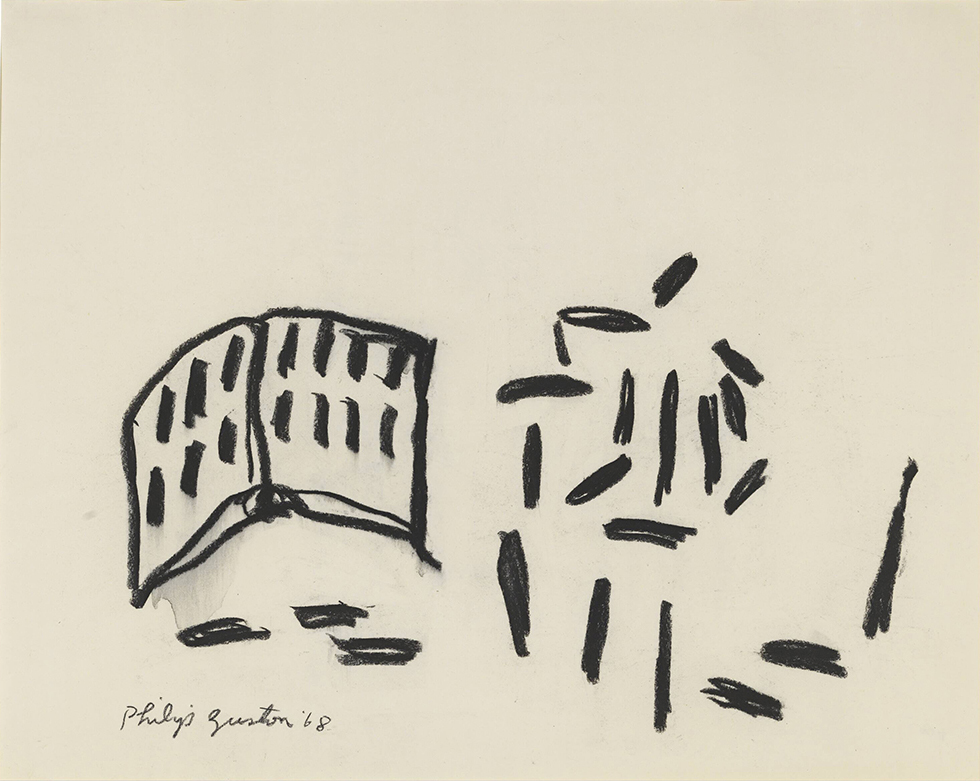

As the art historian Barbara Drudi writes in her essay “Guston and His Italian Contemporaries in Rome,” the year 1948 was a “moment of crisis” for the painter. He even had a large, incomplete canvas which he had begun in America—The Tormentors—shipped to Rome so he could continue working on it in his studio at the American Academy. But he primarily made drawings and did not work on any new series of work, and confessed that “In a sense, I was searching for my own painting.”

After his fellowship, Guston began his praised abstract work. Cooper’s advice to museumgoers? Give proper due to this “central” period of Guston’s career, during which “he was really working out his relationship to paint, to painting, in the most direct way.”

The 1960 Sojourn

Guston next returned to Italy for the 1960 Venice Biennale, in which he showcased his abstract canvases from the 1950s at the United States Pavilion. (As Peter Benson Miller has noted, for decades, general Italian audiences would still associate Guston with the abstract work exhibited at the Biennale, only being introduced to his late style when the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome held a Guston retrospective in 1989.) He traveled around Italy after, spending most of his time in Rome and Florence, but also visiting towns in Umbria and Tuscany, and seeing again some of his favorite Renaissance works. Later Guston wrote an essay for ARTnews about his hero Piero della Francesco, describing the work as presenting “an extreme point of the ‘impossibility’ of painting.”

Greene said his 1960s trip to Italy came at a “classic midlife crisis moment” when he was asking himself if abstraction can adequately respond to the contemporary world. Later in the decade, Guston reached a new juncture in which “he does his most nonobjective work, his ink drawings that are almost pure abstractions,” only to “wipe the slate clean and turn to the recognizable imagery within a year that addresses what he calls ‘the brutality of our times,’” Greene said. This breakthrough led Guston to create the cycle that was shown in the famous 1970 Marlborough Gallery exhibition, where Guston debuted the “hoods” and the monumental cadmium-red-dominated canvases now most associated with the artist.

The 1970–71 Residency

Guston immediately left for the American Academy in Rome following the Marlborough show that shocked the art world. So fast was his escape that he did not see the harsh reviews until after he had arrived in Rome, according to Greene. The sting was mitigated by visiting his beloved Italian art.

In a letter from the Academy in 1971 addressed to ARTnews editor Tom Hess, Guston wrote: “I’ve been going all over Italy, Sicily, looking and thinking. Seeing all the old paintings again, chewing things over and over…Rome, of course, is still Rome but more of a mess than ever—I have never seen so many cars in my life and political fighting. I even started painting again here (small things) now that I’ve gotten over nursing wounds and black despair.”

These “small things” are now called his Roma series: smaller-scale works that are “tender” and “diaristic,” in Greene’s view, offering “a lexicon of sights in Italy, whether it’s the lollipop-shaped umbrella pines or the colossal fragments of the Capitoline Museum.” The peace Guston sought in his Italian sojourn may not have been realized. In the Roma paintings, the hoods seem to emerge from these paintings like ghosts haunting the painter, said Cooper. “Even in paradise—et in Arcadia ego—the hoods are still there.”

Today

Guston’s popularity among artists demonstrates his continuing influence. During the controversy three years ago over the postponement of Philip Guston Now, hundreds of artists signed an open letter in the Brooklyn Rail protesting the decision. According to Cooper and Greene, Glenn Ligon (2020 Resident), Amy Sillman (2015 Resident), Rirkrit Tiravanija, and Terry Winters are among the list of Guston admirers, whether influenced directly by his subject matter, by his painterliness, or by his introspection. Artists have flown from New York and Los Angeles to see the show in Texas. On the penultimate day of the Houston exhibition, Greene said she saw Trenton Doyle Hancock, sitting in a gallery, with a sketchpad.

Postscript

Guston was a Trustee of the American Academy in Rome, and AAR has played a significant role in recent Guston scholarship. Guston’s Roma series, which are not in Philip Guston Now, were exhibited in 2010 and 2011 at Museo Carlo Bilotti-Aranciera di Villa Borghese in Rome and the Phillips Collection in DC in a show curated by Peter Benson Miller that was coorganized by AAR.

In connection with the exhibition, AAR organized a two-day conference in May 2010 with numerous art historians and critics, discussing both the critical and historical reception of Guston’s work and his passion for (and deep knowledge of) Italian art. The conference proceedings became, with additional material, the 2014 book Go Figure! New Perspectives on Guston, edited by Miller and published by the American Academy and the New York Review of Books.

In 2019, AAR announced a new Rome Prize Fellowship named after Philip Guston, established by Musa and Thomas Mayer in memory of Guston.

AAR thanks Peter Benson Miller, Harry Cooper, and Alison de Lima Greene for their time and assistance with this article.