This essay was written by Lindsay Harris, Interim Andrew Heiskell Arts Director, for Winter Open Studios 2022 at the American Academy in Rome, taking place January 27, 2022. Read more about the projects and collaborations being presented by the participating artists.

Openness

The closures caused by the Covid-19 pandemic have underscored the importance of openness in cultural institutions worldwide. For the past two years, museums, libraries, and theaters have done everything in their power to remain accessible to the people they serve. They have also acknowledged that being accessible means far more than simply opening the doors to the building. It means recognizing the systems born of racism and intolerance that stymie an organization, and taking action to create an atmosphere in which everyone can succeed.

At the American Academy in Rome, openness has a long and a relatively short history. The Academy has opened to the public to share Fellows’ work almost since its inception. The First Annual Exhibition of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture was held in New York in 1896, just two years after the Academy was founded. The show highlighted for American viewers the first fruits of Fellows’ encounters with Rome, a city Academy founders deemed “the capital not merely of a country, but of Humanity” and, as such, “the best school” for any artist. Since then, yearly shows of Fellows’ work in an increasing range of disciplines have been held in Rome from 1920 to today. The persistence of these public events, which ceased only briefly during World War II, testifies to the Academy’s commitment to making Fellows’ work accessible to audiences in Rome and beyond.

The work displayed on these occasions chronicles a slower openness to the full sweep of artistic inspiration Rome has to offer, as well as to a wider range of artists from the United States. Figure studies and architectural plans influenced by, or directly copied from, classical models—installed against backdrops of brocade drapes and profuse greenery—dominate the annual shows through the 1930s (fig. 1 above). After World War II, with the arrival of Director Laurance Roberts in 1947, the Academy opened a new chapter of inclusivity. Program requirements were eliminated, encouraging Fellows to immerse themselves in Rome’s infinite lessons, whatever the outcome. Their exploration and experimentation has resulted in an increasingly vibrant range of architectural, artistic, literary, musical, and preservation activity from 1948 to today.

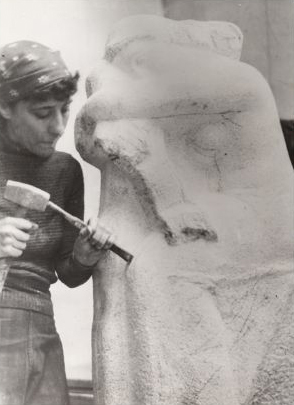

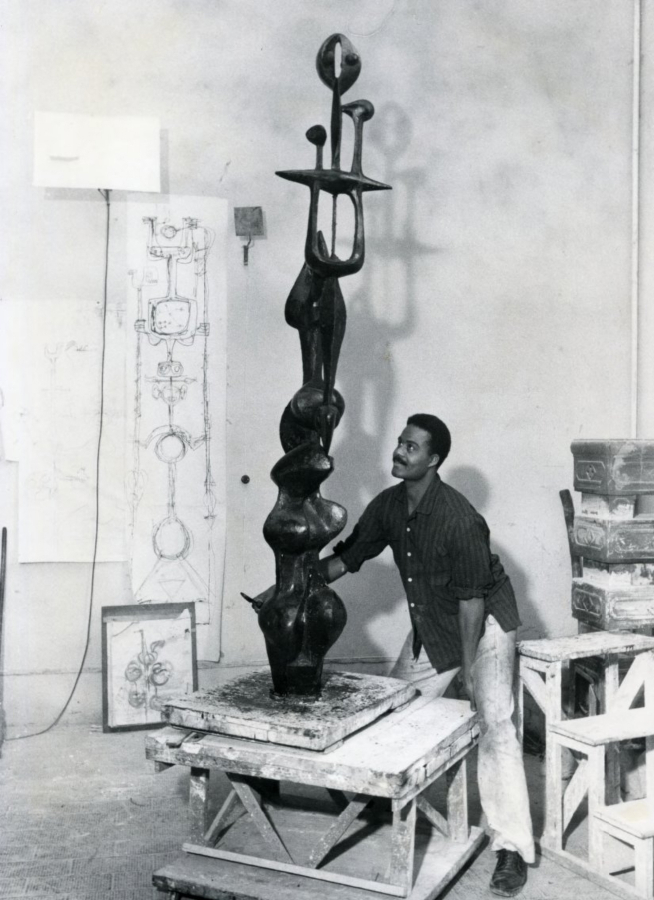

The Academy’s gradual acceptance of varied artistic traditions parallels its openness to diversity among its Fellows. The onset of Roberts’s tenure as Director coincided with the arrival of the first woman to be awarded a Rome Prize in the Arts, Concetta Scaravaglione (fig. 2 above). The fellowship gave her access not only to paintings and sculptures in Rome she had known only from books, but also to the benefits of collaboration. “Here in Italy this collaborative idea is hardly new,” she wrote in a letter in 1949. “This association of creative minds is very evident in the better works of that time and I am finding great enrichment in my work from this atmosphere.” A plaster of one of her better known sculptures, Icarus, ultimately cast in bronze, took center stage at the Annual Exhibition held with the British School at Rome and the Swiss Institute in Rome at Palazzo Venezia in June 1950 (fig. 3 below). In 1948, Ulysses Kay, a composer, became the first Black Rome Prize winner in any of the artistic disciplines pursued at the Academy. Three years later, John Rhoden, a sculptor, became the first Black visual artist to earn a Rome Prize in 1951. At the culmination of his fellowship, in 1954, Rhoden exhibited a towering bronze sculpture whose lithe organicism and integration of figuration and abstraction presaged the style that would characterize his art for years to come (fig. 4 bottom).

The 2022 Winter Open Studios builds on these histories to highlight for audiences in person and online how Rome continues to propel Fellows’ work in new directions. Together, the artists participating in this event have created immersive contexts that broaden their disciplines to foreground women’s voices, diasporic narratives, urban agriculture, new ways of seeing architecture, the legacy of abstraction, the symbiosis between sound and image, and doing nothing. Their accomplishments challenge all of us—including the American Academy in Rome as an institution—to imagine a more inclusive world moving forward, and to do what we can to make such openness a reality.

Winter Open Studios is made possible by the Adele Chatfield-Taylor Fund for the Arts. The program is also funded in part by a grant from the Fromm Music Foundation and in part by the Aaron Copland Fund for Music.